The Great Protocol Wars: How TCP/IP Won the Internet

Part 1 of “Down to the Wire” - A series exploring the networking fundamentals that power our connected world

When your microservice can’t reach the database, you instinctively follow the same troubleshooting playbook: check network connectivity, verify DNS resolution, examine application logs, maybe peek at TCP connection states. The debugging approach of working from the network layer up through the application stack exists because of a technical battle that ended 30 years ago but still shapes every packet flowing through your infrastructure today.

Right now, developers are living through a similar conflict. GraphQL evangelists argue it’s superior to REST in every measurable way: better performance through precise data fetching, stronger type safety, more flexible queries. Meanwhile, REST continues to dominate because it’s simple, well-understood, and already deployed everywhere. Sound familiar?

This same pattern played out on a much larger scale during the “Protocol Wars” of the 1970s-1990s, when the future of computer networking hung in the balance. The outcome of this technical battle determines why you debug network issues the way you do, why your containers can communicate across data centers, and why the Internet exists at all.

When Networks Were Islands

Before diving into the technical battle, let’s set the scene. In the early 1980s, getting two computers from different vendors to communicate was like trying to fill a Tesla up with premium at the local gas station. The infrastructure just wasn’t compatible.

IBM’s Systems Network Architecture (SNA) dominated corporate computing, processing an estimated 70% of the world’s network traffic by 1985. If you worked for a Fortune 500 company, your green-screen terminal almost certainly spoke SNA to a mainframe somewhere. Meanwhile, Digital Equipment Corporation’s DECnet connected approximately 25,000 minicomputers in a peer-to-peer fashion that was actually decades ahead of its time. Novell’s IPX/SPX ruled local area networks with zero-configuration networking that made even AppleTalk’s plug-and-play design look clunky. By 1990, Novell claimed 65% of the LAN server market.

Each system worked beautifully within its own ecosystem. SNA networks achieved 99.9% uptime in enterprise environments. DECnet offered sophisticated routing and network management that wouldn’t look out of place in a modern data center. IPX/SPX delivered LAN performance that often exceeded early TCP/IP implementations.

But connecting them? That required expensive gateways costing $50,000-$200,000, protocol translators that introduced latency and failure points, and a small army of network engineers who specialized in making incompatible systems talk. A typical Fortune 500 company might spend $2-5 million annually just on protocol translation equipment.

It was like having an internet where you needed different apps to message iPhone users, Android users, and Windows users. Actually, wait…we tried that. Remember Google Wave?

The Contenders: TCP/IP vs. OSI

Into this fragmented landscape came two radically different visions for universal networking. Understanding their technical philosophies explains why we architect distributed systems the way we do today.

TCP/IP: The Scrappy Underdog

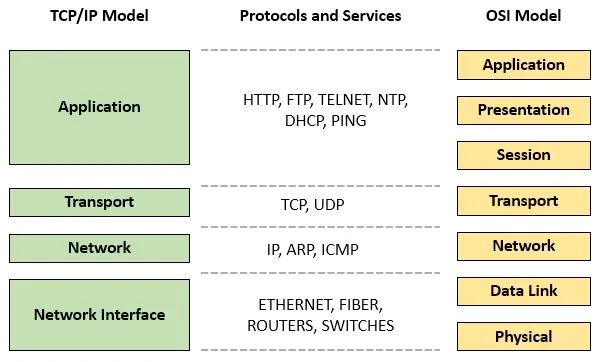

TCP/IP emerged from DARPA’s research community with a deceptively simple four-layer model:

Application | Your code lives here (HTTP, MQTT, SSH)

Transport | TCP/UDP - reliability and ports

Internet | IP - addressing and routing

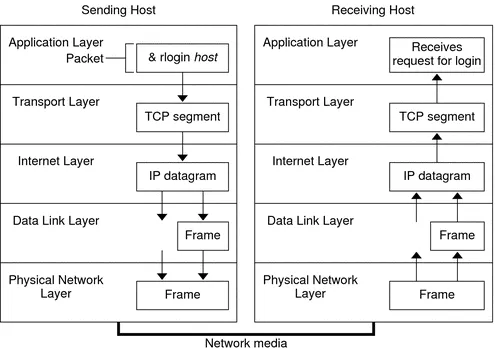

Link | Ethernet, WiFi - the physical stuffThe genius was in what TCP/IP didn’t do. Instead of trying to solve every networking problem, it followed what became known as the “end-to-end principle”: keep the network core simple and stupid, push intelligence to the edges.

This philosophy directly impacts how you build systems today. When you’re troubleshooting that MQTT connection drop, you’re seeing this principle in action. The network doesn’t know or care about your application-level heartbeats, session state, or business logic. It just moves packets reliably from point A to point B. Your application handles the complexity of reconnection strategies, message deduplication, and state recovery.

OSI: The Perfect Standard

The Open Systems Interconnection model took the opposite approach. Designed by international committees with representatives from major telecommunications companies and governments, it created seven perfectly separated layers:

Application | Network services to applications

Presentation | Data formatting, encryption, compression

Session | Managing connections between applications

Transport | End-to-end message delivery and error recovery

Network | Routing packets through intermediate nodes

Data Link | Node-to-node delivery of frames

Physical | Transmission of raw bits over physical mediumOSI was theoretically elegant. Each layer had a precisely defined role with clean interfaces between them. It supported both connectionless and connection-oriented communication, included sophisticated addressing schemes that could scale to any conceivable network size, and provided comprehensive error handling and recovery mechanisms.

If TCP/IP was a motorcycle, simple, fast, and effective, OSI was a luxury sedan with every feature you could imagine, from heated seats to a built-in navigation system.

The Technical Battle: Why “Good Enough” Won

Here’s where it gets interesting. By almost every technical measure, OSI should have won. It was more comprehensive, more rigorously standardized, and backed by major corporations and governments with deep pockets. The European Union mandated OSI for all government systems by 1990. Even the U.S. Department of Defense, TCP/IP’s original sponsor, announced plans to migrate to OSI by 1995.

Industry analysts predicted OSI would capture 80% of the networking market by 2000. Major vendors like IBM, Digital, and AT&T invested billions in OSI development. Universities taught OSI as the “right” way to think about networking.

So why are you reading this on a TCP/IP network instead of an OSI one?

Performance: Pragmatic Violations vs. Pure Architecture

TCP/IP’s dirty secret was “layer violations”-cases where implementations broke architectural purity to solve real-world problems. OSI purists considered this heresy. TCP/IP engineers considered it Tuesday.

Example 1: Application-aware TCP optimization. Modern TCP implementations often examine application data patterns to make performance decisions. When Netflix streams video, the TCP stack might adjust its congestion control algorithm based on recognizing video streaming patterns, or prioritize certain packet types. Technically, this violates the clean separation between transport and application layers, but it dramatically improves user experience. QUIC was explicitly created as an alternate transport protocol that optimizes streaming content.

Example 2: Network Address Translation (NAT). When IPv4’s 4.3 billion addresses started running out in the 1990s-something the original Internet pioneers didn’t fully anticipate-NAT emerged as a pragmatic band-aid. NAT devices routinely examine and rewrite TCP and UDP headers, blatantly violating the separation between network and transport layers. An OSI purist would be horrified, but NAT kept the Internet growing when the “proper” solution (IPv6) wasn’t ready for deployment.

Example 3: Modern load balancers. Today’s application load balancers operate at multiple layers simultaneously. They examine HTTP headers (Layer 7), manipulate TCP connections (Layer 4), and make routing decisions based on IP addresses (Layer 3) all in the same device. This architectural “mess” delivers the performance and flexibility that powers modern web applications.

OSI’s strict layering prevented these kinds of creative workarounds. Every piece of data had to flow through every layer in order, with formal interfaces between each. This created performance bottlenecks that became more apparent as network speeds increased, and made it nearly impossible to adapt to unforeseen challenges like address exhaustion or the emergence of multimedia applications.

Complexity: Working Code vs. Perfect Specifications

While OSI committees were perfecting specifications, TCP/IP engineers were shipping code. The University of California, Berkeley released BSD Unix with a complete TCP/IP implementation that anyone could download, compile, and deploy. Want to add TCP/IP to your system? Here’s working source code, complete with examples and debugging tools.

OSI had detailed specifications describing every protocol detail across dozens of documents. But turning those specifications into working code was left as an exercise for the implementer. Early OSI implementations were complex (often requiring 2-3x more code than equivalent TCP/IP functionality), slow (benchmarks showed 30-50% performance penalties), and often incompatible with each other despite following the same specification.

This pattern repeats constantly in software development. How many times have you chosen a library with good documentation and working examples over one with perfect theoretical design but sparse documentation? The developer experience often trumps technical superiority.

Economic Reality: Free vs. Expensive

The economics were brutal and decisive. TCP/IP implementations were free. Berkeley’s BSD Unix included a complete networking stack at no additional cost. OSI specifications themselves cost money, sometimes significant money. The complete OSI specification set cost $2,000-$5,000 in 1980s dollars. IBM’s SNA software licenses could cost $10,000-$50,000 per month for high-end systems. Even downloading basic OSI protocol definitions from international standards bodies required membership fees or per-document payments.

For hardware vendors, the cost difference was even more stark. Adding TCP/IP support to a product meant hiring a few engineers familiar with Berkeley Unix. Adding OSI support meant purchasing specifications, attending expensive standards meetings in Europe, navigating complex licensing agreements, and often paying royalties to patent holders.

The economic impact was immediate and measurable. A startup could implement basic TCP/IP networking for the cost of a computer science student and a $500 Unix license. Implementing equivalent OSI functionality required a $50,000+ investment before writing a single line of code.

Sound familiar? It’s the same dynamic that made Linux competitive against commercial Unix systems, why REST APIs dominated over SOAP web services, and why open source databases are eating into Oracle’s market share.

Lessons for Modern Developers

The TCP/IP Principles for Today’s Architecture

The Protocol Wars offer timeless lessons for anyone building distributed systems:

-

Simplicity scales better than completeness. Your API design benefits from the “TCP/IP principle”-do one thing well rather than trying to solve every problem.

-

Reference implementations beat perfect specifications. Developers adopt technologies they can immediately use. This is why successful open source projects include working examples, not just documentation.

-

Economic accessibility drives adoption. The total cost of adoption is encompassed by the learning curve, tooling, licensing. These three often matter far more than technical superiority.

-

“Good enough” deployed beats “perfect” in development. The Internet runs on protocols that their creators knew were imperfect, but they shipped and iterated rather than holding committee meetings.

The Tipping Point: How Network Effects Compound

The technical and economic advantages might not have been enough if not for a crucial catalyst: strategic government investment that created an unstoppable network effect.

The ARPANET Mandate: Forced Adoption

On January 1, 1983-known as “Flag Day”-DARPA issued an ultimatum to all ARPANET hosts: switch from the old Network Control Protocol (NCP) to TCP/IP or lose network access. Overnight, every computer connected to the predecessor of the Internet had to speak TCP/IP.

DARPA had spent roughly $500 million over two decades (approximately $1.5 billion in today’s dollars) funding TCP/IP development at universities and companies across the United States. Key contributors included:

- UC Berkeley: $50 million in funding over 10 years for BSD Unix development

- Bolt, Beranek & Newman (BBN): $200 million for ARPANET infrastructure and TCP/IP implementation

- Stanford Research Institute: $30 million for protocol research and testing

- Various universities: $100+ million in distributed research grants

They weren’t about to abandon that investment for an international standard they couldn’t control and that offered uncertain benefits.

The Network Effect Snowball: Exponential Adoption

The numbers tell the story of how network effects compound:

1983: 500 ARPANET hosts, all running TCP/IP by mandate 1984: 1,000 hosts (2x growth as universities connected) 1986: 5,000 hosts (5x growth as regional networks joined) 1988: 50,000 hosts (10x growth as commercial adoption began) 1990: 300,000 hosts (6x growth as ISPs emerged) 1992: 1 million hosts (3x growth as web adoption accelerated)

Once TCP/IP had critical mass on ARPANET, connecting to the network required TCP/IP compatibility. Universities wanting to access ARPANET resources for research implemented TCP/IP. Companies wanting to sell to those universities added TCP/IP support to their products. Regional networks that wanted to connect to ARPANET adopted TCP/IP as their backbone protocol.

Each new connection made the network more valuable to the next potential adopter. By 1987, ARPANET carried more inter-organizational traffic than all commercial networks combined. By 1990, if you wanted to connect to what was becoming the Internet, you needed TCP/IP. OSI networks became isolated islands in an increasingly connected world.

Meanwhile, OSI suffered from coordination problems that prevented network effects from taking hold. The European X.25 networks ran OSI protocols but remained largely isolated from each other due to political and technical disputes. Corporate OSI implementations were expensive and often incompatible. There was no central coordinating authority like DARPA to mandate adoption and fund development.

The Microsoft Parallel: Platform Lock-in Effects

This dynamic mirrors what happened with operating systems in the 1990s. Windows wasn’t technically superior to OS/2, BeOS, or even Linux in many respects. But once Windows achieved critical mass, software developers targeted Windows first, which made Windows more valuable to users, which attracted more developers-a virtuous cycle that proved nearly impossible to break.

The same pattern is playing out today with cloud platforms, container orchestration systems, and even programming languages. Once a technology achieves network effects in a critical community, switching costs make alternatives increasingly difficult to adopt, regardless of their technical merits.

Modern Echoes: What We Can Learn

The Protocol Wars illuminate patterns that repeat across every layer of the technology stack:

Network effects compound exponentially, not linearly. TCP/IP’s adoption curve shows how quickly a technology can go from niche to dominant once it reaches a tipping point. Modern examples include Docker’s container format becoming the de facto standard, or how React achieved dominance in frontend frameworks despite Angular having early market leadership.

Strategic institutional backing can create artificial network effects. DARPA’s mandate gave TCP/IP the critical mass it needed to trigger organic adoption. Today, we see similar patterns when major companies (Google with Kubernetes, Facebook with React) invest heavily in open source projects and drive adoption through their ecosystems.

Economic accessibility often trumps technical superiority. Free and “good enough” consistently beats expensive and “perfect.” This explains the success of MySQL vs. Oracle, Linux vs. Unix, and countless other technology adoption stories.

Architectural flexibility enables evolution. TCP/IP’s willingness to embrace “layer violations” allowed it to adapt to unforeseen challenges like NAT, mobile networks, and content delivery networks. Rigid architectures, no matter how well-designed, struggle to adapt to changing requirements.

Next time you’re architecting a distributed system, choosing between competing technologies, or wondering why certain “inferior” solutions dominate their markets, remember: you’re seeing the same forces that shaped the Internet’s foundation playing out in miniature.

The Internet runs on protocols that their creators knew were imperfect. But they shipped, iterated, and adapted-while their competitors held committee meetings.

The Strange Victory of OSI: Why We Still Use Layer Numbers

Here’s a fascinating paradox: OSI lost the protocol war completely, but won the conceptual war so thoroughly that we still use its terminology today. When you talk about “Layer 7 load balancing” or debug “Layer 4 connectivity,” you’re using OSI’s seven-layer model to describe TCP/IP networks.

This happened because OSI solved a real problem that TCP/IP’s four-layer model couldn’t address: teaching and troubleshooting complex networks.

The Educational Problem

TCP/IP’s four layers were perfect for implementation but terrible for explanation. When a network engineer said “it’s an application problem,” that could mean anything from HTTP header issues to database connection pooling to DNS resolution. The troubleshooting process lacked precision.

OSI’s seven layers provided a much more granular diagnostic framework:

- Layer 1 (Physical): “Are the cables plugged in? Are the fiber optics clean?”

- Layer 2 (Data Link): “Is the switch forwarding frames? Are we seeing MAC address conflicts?”

- Layer 3 (Network): “Can we ping the destination? Are there routing loops?”

- Layer 4 (Transport): “Are the TCP connections established? Are we hitting port limits?”

- Layer 5 (Session): “Are the TLS handshakes completing? Are we maintaining session state?”

- Layer 6 (Presentation): “Are we handling character encoding correctly? Is compression working?”

- Layer 7 (Application): “Are the HTTP headers correct? Is the application logic functioning?”

The Troubleshooting Victory

By the 1990s, network engineers had adopted OSI’s layer model as a troubleshooting methodology while still running TCP/IP protocols. Cisco’s networking certifications taught OSI layers as the standard diagnostic approach. Network monitoring tools organized their displays around OSI layers. Firewall vendors marketed “Layer 7 inspection” capabilities.

This created a bizarre but practical hybrid: OSI thinking, TCP/IP doing.

When you see a modern network diagram showing “Layer 4 load balancers” and “Layer 7 application delivery controllers,” you’re seeing this hybrid in action. The load balancer is running TCP/IP protocols, but we’re using OSI’s conceptual framework to describe what it does.

The Irony of Standards

OSI’s lasting contribution wasn’t its protocols-it was its mental model for understanding network complexity. The seven-layer framework became so useful for education and troubleshooting that it transcended the specific protocols it was designed to describe.

This is perhaps the ultimate irony of the Protocol Wars: the “losing” standard became the universal language for discussing the “winning” standard. TCP/IP conquered the networks, but OSI conquered the minds.

Coming up in Part 2: We’ll explore the magic behind global content delivery—how the same server can exist everywhere at once through anycast routing, BGP wizardry, and the complex web of ISP relationships that make CDNs possible. Plus: what it actually takes to build your own CDN.

Sources and Further Reading

This post draws from extensive research into the Protocol Wars and early Internet development:

- Russell, Andrew L. “Open Standards and the Digital Age: History, Ideology, and Networks” - provides crucial context on how Internet standards development differed from traditional telecommunications approaches

- IEEE Spectrum’s detailed analysis “OSI: The Internet That Wasn’t” offers technical insights into why OSI failed despite institutional backing

- The Internet Society’s historical archives document the transition from ARPANET to modern Internet protocols

- DARPA funding records and congressional budget documents provide specific investment figures for TCP/IP development

- Market research reports from Gartner and IDC (1980s-1990s) document adoption rates and economic impact

- Glenn Ricart’s contributions are documented through the University of Maryland Computer Science Department archives and his Internet Hall of Fame induction materials

- Economic analysis of the Protocol Wars comes from “The Battle Between Standards: TCP/IP vs OSI” published in research on technology adoption patterns

For developers interested in deeper technical details, the original IETF RFCs (especially RFC 1123 which established the complete Internet protocol suite in 1989) provide fascinating insight into the engineering decisions that still influence our work today.